I WENT TO MONGOLIA

In July 2018, I traveled to Mongolia. There I reconnected with old friends, made new ones, learned a good deal of history and bore witness to some of the most beautiful land our planet has to offer. Here are my photos and experiences.

Some years ago, I picked up Jack Weatherford’s excellent book, “Genghis Khan and the Making of the Modern World” on a free Audible credit. That book sparked a long-standing interest with the country and history of Mongolia and central Asia in general.

In the past few years, I’ve had the privilege of making a number of Mongolian friends in the Washington D.C. area (suburban Arlington has, I believe, the largest Mongolian diaspora in the world). I’ve even picked up cursory bits of the language, but my vocabulary is relegated primarily to food items, basic greetings and compliments. It’s more than most Americans know, though, so even a simple greeting—Сайн байна уу?—is sometimes enough to show that I’m at least trying.

And so in Summer 2018, I decided it was time to see Mongolia for myself.

The Steppe

- I spent a good part of my time in the country in the passenger seat of an SUV. I stared out the window as we barreled down the highway on the Mongolian steppe at about 120 kph. We went from Ulaanbaatar, the capital, until we were nearly to Kazakhstan.

- As I traveled across the steppe, it seemed in the very best way like it could never end. It stretched in every direction. It was a sea of grass, rolling hills and sparse patches of scrub, dotted occasionally with gers, herdsmen and their animals. My companions’ playlist consisted mostly of Mongolian folk and country songs that (after hearing them countless times) I was quietly singing along with by the time we returned to the city. Of course, I only understood every fourth word or so, but I was able to understand the general idea.

- There was something very captivating and irreplaceable about this experience—staring out the window at grass, patches of color, otherworldly rock formations, lazily grazing herds and blue skies for days.

- Most of the highway through the steppe looked exactly like this—reasonably well-maintained asphalt roads, animals always grazing in the background, and a power lines running off into the horizon to provide commercial power to villages and ger camps throughout the steppe. The paved roads were not continuous; sometimes we’d have to negotiate our way up and back down rutt-filled trails on muddy hills when the pavement would abruptly stop, and sometimes, we'd just have to make our own way through with no trail at all.

- We stopped at ger camps along the way—we could rent a ger for about $30 USD that provided accommodation enough for the six of us. The host will get your wood stove going and bring extra blankets when it’s cold (it will also be cold at night in Mongolia, even in July). You’ll sleep on a raised bed. Some camps had running water, and in one case, a shower. I saw a variety of tour groups featuring a stay in a ger as if it were part of some exotic adventure at the end of the earth; in reality, you're hardly roughing it.

- The ger camps struck me as not much different from a roadside motel or hostel. But there was something unusually cozy and relaxing about sleeping together in a ger with friends, huddled around a crude wood stove during the chilly summer nights. I can’t recall the last time I have slept so well. The Mongolian people love their gers, not only as practical housing, but as a symbol of their history and the honor of their culture. After staying in them, I can see why. I can't articulate exactly why, but I have developed a fondness for gers as well.

- The name of this national park escapes me, but it was the most pleasant place that we stayed on our journey. It was a fairly typical camp, but the weather and scenery were particularly nice. There were herds of horses and cows wandering around as if they owned the place, and I did wonder where were the ranchers that owned them.

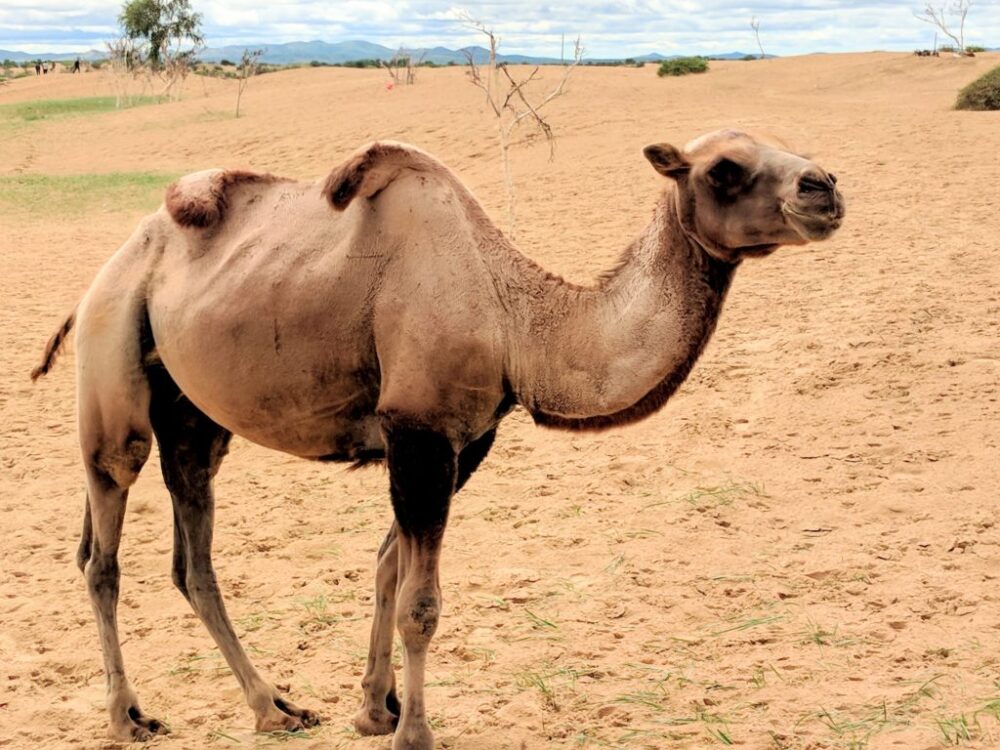

- At one point we took a detour near the mouth of the Gobi desert. Mostly for novelty's sake, we pulled over, rented a half dozen horses and camels and goofed off in the sand for awhile. I had never ridden a camel prior to this. I found that they are comfortable and easy to ride, but extremely stubborn, and when they whine, they sound exactly like you would imagine a person sounds when making fun of a stubborn camel. I was much too tall for the stirrups that our animals were outfitted with, so I had to leave my feet dangling.

- Turuu did most of the driving. He thankslessly spent days behind the wheel, and I was beyond impressed with his handling of our SUV off-road. At one point, I was absolutely certain we would have to abandon our truck, having been caught in a rainstorm, inundated with mud on the side of a mountain. Somehow, he not only got control of the car, but forced it up the muddy slope in a zigzag pattern until we reached the shrine at the summit. Everyone poured out of the car to make three circles and pray, making an offering of food. In prayer, he offered vodka made from milk.

- Every vehicle in Mongolia is a Toyota, and most of them are a Toyota Prius hybrid, some of them dating back to the original 1997 model. People in Mongolia drive their Priuses everywhere; after a day or two of conditioning, it did not strike me as unusual, for example, when I saw someone utilizing a Prius to ford a river.

- In recent years, owing to a combination of climate change and overgrazing, the Gobi has been growing as parts of the steppe gradually succumb to desertification. The steppe’s grasslands are fragile, with sandy topsoil that seemed like it might have been a centimeter thick. Disruptions in the ecosystem, whether from increased soil erosion from climate change or the increasingly large goats herds that tear at the roots, are slowly but inexorably converting the steppe's grass and brush to desert. As a good half of this country’s population depends directly on livestock in one way or another for their livelihood, the spread of the desert presents a major economic issue for the future. Nonetheless, the world has an insatiable demand for Mongolian cashmere, and more cashmere means more goats, and it seems unlikely the human race will get its arms around human-influenced climate change anytime soon. Further, climate change has led to shorter and drier rainy seasons while the winters are colder and longer. This leads to mass dyoffs of livestock, called Зуд ("Zud"). Each zud used to occur about once per decade; in the 21st century, they are much more frequent and recently occurred three times in a row (1999-2002), breaking dieoff records previously set in the 1940s. A little searching online can yield countless case studies where a family lost their entire herd (and accordingly, accumulated wealth) to a zud and was forced to move to the city to try and find work. However, even knowing the facts in this case and seeing the evidence in front of me, as I stood at the mouth of the Gobi with the endless sand before me and the endless grass behind me, I couldn’t help but feel as I stood there that the steppe was infinite and invincible, and that it would stand forever.

So Many Creatures

- There are many times more livestock than people in Mongolia; estimates vary by source that I referenced, but a country of 3 million people has 50 million or more head of cattle, sheep, yak or goat. You see this throughout the countryside, and where I was at first delighted to see a herd of horses wander nonchalantly into my camp to graze in the morning, by the time I returned to Ulaanbaatar from the countryside, I was fairly numb to the sight of these ubiquitous creatures.

- Mongolian horses are smaller, but sturdier, than the Iberian horses in North America brought by the Spanish during the 1400s-1500s. Owing to their powerful physiques I would not exactly call them ponies, but other than their impressive musculature they are roughly the same size as one.

- Back home in Wisconsin, deer are everywhere, and they are a nuisance and threat on the road. Everyone in my hometown has had an experience where they've hit a deer or ran off the road avoiding one, wrecking their car or being injured. And so when driving, you are always watching for deer and routinely have close calls on highways. In only a few days on the road here, I developed this same relationship with horses. What an unfamiliar feeling: to be surrounded by so many horses that they were nearly a pest.

- A regular fact of life in Mongolia outside of Ulaanbaatar is that you are going to have to stop your car when a herd wanders onto the road in front of you. This will happen all of the time. There are generally no fences or boundaries as the herds move freely across the steppe to graze. The animals are totally comfortable around cars, and sometimes stubbornly refuse to move out of the way even as you are blaring your horn. I got the distinct impression that the land was reserved for animals first, and cars second.

- There is really no concept of grass-fed, all-natural, no-hormone, free range meat here, as that is just the standard meat available everywhere. Though my western palate had some trouble adjusting to the idea of steak cooked nearly all the way through, that is just how it is served here. Even well-done, I found Mongolian meat to be the best in the world.

A Day at the Beach

We spent one morning and early afternoon leisurely goofing off in and around Terkhiin Tsaagan Lake, about 400-500 miles’ drive west from Ulaanbaatar. It’s one of the only places in the entire country I’ve seen a restriction on where one could set up camp–in this case, you had you pitch your tent at least 20 feet or so from the beach.

Otherwise, best as I can tell, you are free to stand up up your tent (or ger) on nearly whichever inch of this vast and beautiful country you would like to.

- My friends Uugi and Khishigee goofing around in traditional clothes.

- The water was immaculately clean and beautiful. Of course, it was just my luck that I contracted a horrible skin infection from some parasite in the water that dogged me for the following few days, and the lower half of my body was covered with oozing lumps. Nobody else in the group was affected.

- I asked my friends about the significance of these carefully piled rocks, assuming some cultural or religious purpose. The only purpose, in fact, was just that it looks nice.

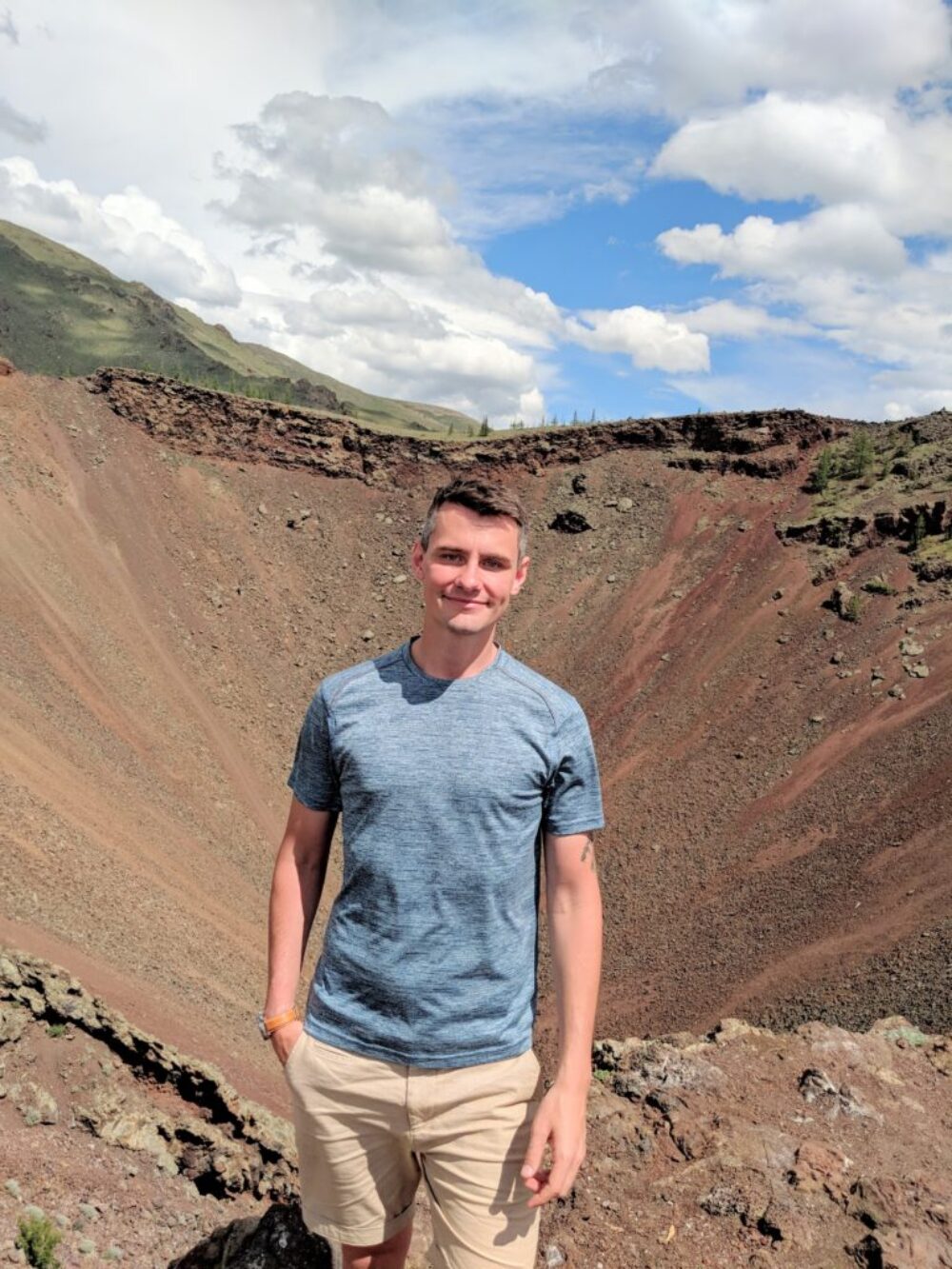

Khorgo Volcano

In a nation of such seemingly limitless natural and scenic beauty, it seems ridiculous, frankly, to designate any one particular area as protected land. However, Khorgo Mountain, a dormant volcano in Arkhangai province, struck me as worthy of the protected status it has held since 1965.

The volcano erupted about 8000 years ago, flooding the valley with magma and peppering the surrounding region with countless black boulders and stones of basalt rock. Owing to this geologic event, the region now carries unique flora and fauna including an evergreen forest populated with deer, ducks and wild boar. The hike up to the lip of the crater is manageable even for a novice hiker and offers outstanding views of the Taryatu-Chulutu volcanic field.

Buddhism

Once cannot investigate Mongolian culture and history without considering the important role of Buddhism—not only as a cultural and religious institution, but as a political and historical one.

There is evidence that Buddhism was first introduced to the Mongols as far back as the 4th century, but it would not become central to Mongolian history until the 13th century, when Kublai Khan practiced and clearly favored Buddhism. After the fall of the Kublai’s Yuan dynasty, Buddhism experienced a brief decline until later in the 16th century, when feudal lords and herdsmen began to convert to Buddhism en masse. Eventually, thousands of monasteries were built throughout the city, and at one point, as much as about half of the male population of Mongolia consisted of Buddhist monks and over 2000 monasteries were constructed throughout the countryside.

From the late 1500s and until the era of Soviet control in the 20th century, Buddhist monasteries functioned as much as political entities just as much as they did religious ones, controlling much of the wealth, order and legitimate control of society in the country.

The widespread Soviet-led purge of Buddhism in the 1920s eliminated any legitimate control Buddhist leaders had over the function of society. Mongolia established a democratic government in a series of reforms through 1990-1992, and today, Mongolia is a modern country led by elected officials. Today, most residents of Mongolia are practicing Buddhists.

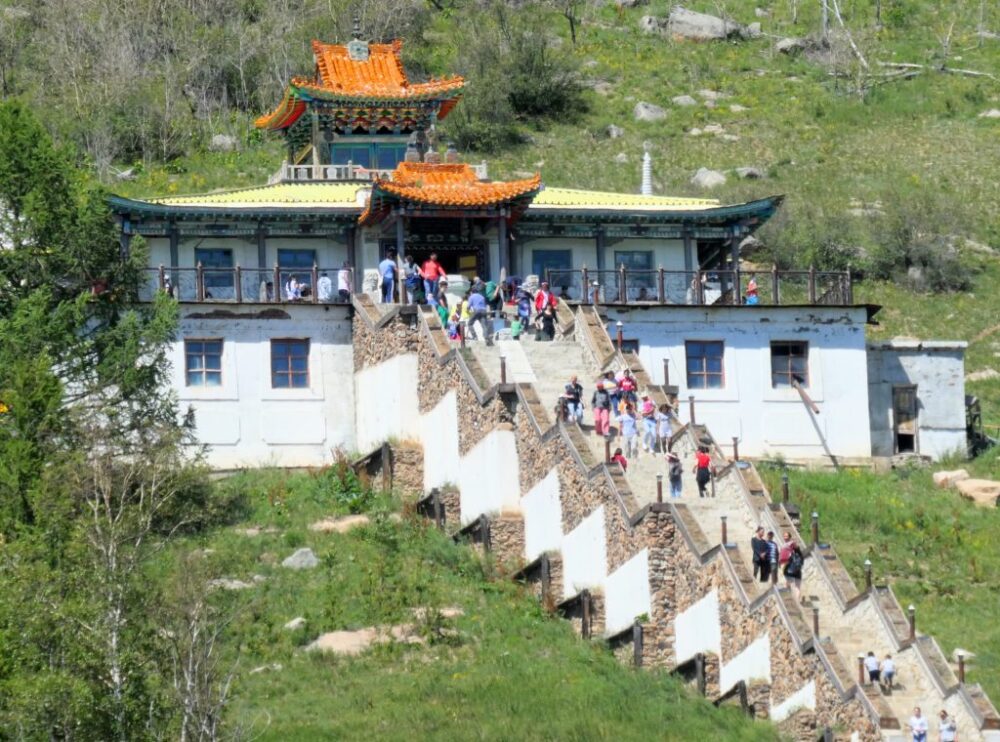

Some old temples and monasteries stand today, serving a dual role as tourist attractions as well as places of worship. As my friends and I traveled through, we both seemed equally welcome as I admired the art and history of these and my friends stopped to pray.

- The Ariyabal Meditation Temple in Gorkhi Terelj National Park was by far the most crowded temple we visited, but it was absolutely lovely. I didn’t feel comfortable taking many photos of the stunning art here or in most of the other temples I visited, because even though in those rare cases that photography was not forbidden, it seemed somewhat crass to take tourist photos in a place of worship.

- One of the gates at the Bogd Khan Winter Palace, much of which is intact today a few miles from downtown Ulaanbaatar. This place and some of the other temples I visited struck me as the most peaceful and isolated places on the planet; in this case, it felt so peaceful even in Mongolia’s capital a block away from the national stadium. It was raining a lot while I visited, and most people had left town for the holiday, and I was on vacation, so maybe it there were a confluence of factors. But it was special to me.

- Bogd was the last person awarded the title of Khan. Born in Tibet in 1869, as a boy he was recognized as the Bogd Gegen, the top-ranked lama, or head of religion, for Mongolia. He subsequently moved to the country at the age of 5 and spent the rest of this life there. On December 29, 1911, amidst the collapse of the Qing Dynasty and decline of Imperial China, Bogd Gegen was declared Khagan of Mongolia, taking the title of Bogd Khan. He would be the last of the khans, his shortly-lived theocracy was lasting only until 1919, when Chinese troops would occupy the country once again.

- For the next five years, Mongolia became a battleground for powers both foreign and domestic, trading hands between Bogd Khan loyalists, Chinese forces, anti-Bolshevik Russian revolutionaries and ultimately the Soviet Union. The Soviet-backed Mongolian People’s Republic was established in 1924. It functioned in almost all respects as the 16th unofficial republic of the Soviet Union. Mongolia was, at least officially, a sovereign nation and served for much of the 20th century as a strategic buffer between Soviet and Chinese territory.

- The Soviet-backed Mongolian People’s Republic was established in 1924. It functioned in almost all respects as the 16th unofficial republic of the Soviet Union. Mongolia was, at least officially, a sovereign nation and served for much of the 20th century as a strategic buffer between Soviet and Chinese territory.

- A stupa at Erdene Zuu Monastery, which by most records is most likely the oldest surviving monastery in Mongolia. It was constructed in the late 1500s, but was badly damaged in war and abandoned around 1688. It was later rebuilt and by the beginning of the 20th century housed about 1000 monks. Note the yellow and blue Soyombo symbol painted on the stupa at the left, with partial sculptures of it at the top. This symbol was created by Mongolia's religious and cultural hero, Zanabazar, in the 1600s, and is featured on the nation's flag today. It is the national symbol of Mongolia. Its component parts represent the sun, moon and fire, past present and future, the defeat of one's enemies, the honor of justice of Mongolia's people, unity and strength between people and finally, the balance between man and woman.

- It would have been destroyed if not for the unlikely intervention of Joseph Stalin in 1944. This monastery was targeted, along with many others, in the widespread purge of organized religion conducted by the fledgling communist Mongolian People's Republic. Stalin intervened, convincing the government to maintain the temple as a feigned example to foreign visitors that the nation permitted freedom of religion. It is a complete farce, but I suppose the outcome was positive, because the monastery was spared complete distruction.

- Though most of the monastery was demolished prior to this, a few small temples and stupas remain, including this one, and as of 1990, Erdene Zuu serves a dual function as a modest functioning monastery as well as a museum today.

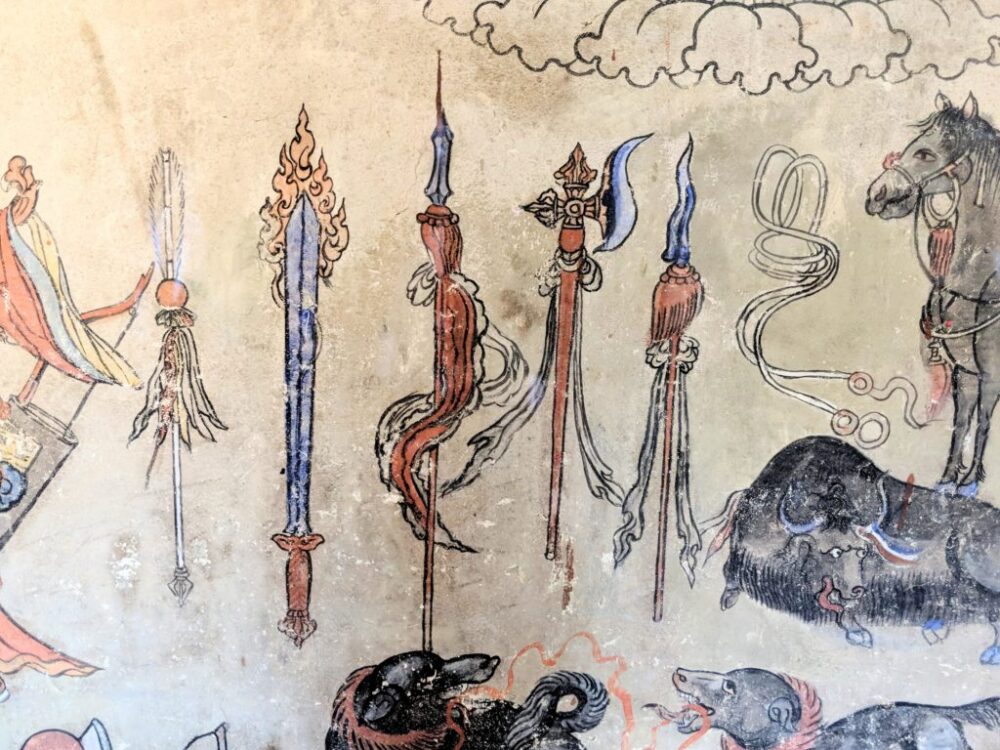

- Mongolian Buddhist art carries a certain ferocious spirit; deities and historical figures are often depicted powerfully and with an assortment of weapons.

- And in every temple, of course, was a Buddha.

Saikhaan Naadaarai

Naadam is Mongolia’s largest cultural festival and holiday, occuring every summer for three days. While the festival traditionally is centered around the nation’s three traditional sports–wrestling, archery, and horseback riding–in Ulaanbaatar, while these sports were certainly well-represented, the experience of being there was not much different than any other national festival. There were concerts, fireworks, street vendors and performers, fried food, long waits at temporary toilets and, of course, crowds.

I was tremendously excited prior to my trip, feeling it was an honor to visit Mongolia during Naadam. Before I went, I had thought it would be the highlight of my trip. However, when I came home and began looking back through my photos, I noted that I had barely taken any of them at the three-day festival. It was a great privilege to see Naadam, but the best memories I had during my trip all took place outside of it.

- The festival was by a long shot the only crowded place I was able to find in the entire country. I do not think it is an overstatement to claim that all 3 million of Mongolia’s residents join a few hundred thousand tourists to all cram into the same city block for the opening ceremony on the first day of Naadam. And they are there the second day about a mile’s drive (and three hours in traffic) at the racetrack outside of town.

- Speaking of tourists, not so many Americans have visited Mongolia, and so most of my friends thought it a very strange place to visit. However, Ulaanbaatar was choked with international tourists my entire time there. During my stay I was one of thousands of westerners wandering around the city. Accordingly, Mongolia has a thriving tourism industry, and even if I hadn’t been spending my time with gracious friends willing to drive me and show me around, there would have been countless professional guides and organized tours available to me.

- In one case, I attended a show where I am reasonably certain the only resident of Mongolia in the entire audience was my Tinder date. The performance was, of course, narrated in English.

Life in Mongolia

Ulaanbaatar is the capital of Mongolia, and practically speaking, the country’s only city (the second largest city, Erdenet, has only 83,000 residents). About half of the country’s 3 million people live here in Ulaanbaatar.

Through most of the 20th century, Mongolia was not an official member of the Soviet Union, but it was more or less under Soviet control and a sort of unofficial member of the republic. Today though, outside of the primary alphabet used (Cyrillic), a handful of old monuments and some aging apartment buildings, there is very little of the country’s soviet history on display. I wondered while I was there if any Soviet character the country had has been suppressed on purpose in order to establish a new Mongolian identity, or if it just was never part of the culture the way it is, for example, in Kazakhstan.

Mongolia established a Democratic government and market economy through 1990-1992, finding its way into the modern world like many other countries did during the collapse of the Soviet Union. Though Mongolia is a developing country with many of the same economic and social challenges as its peers in the developing world, It has on average been one of the fastest-growing economies in the world for 20 years.

The vibrant capital lies at a confluence of eras, featuring brutally efficient old Soviet concrete towers, Russian-style opera houses, soaring asymmetrical glass towers, ancient Buddhist temples and not a small number of gers. Further, it seems like the city is the middle of a constant complete teardown and rebuild as the city’s population swells by about 5% every year and infrastructure struggles to keep up.

For the most part, though, it was not unlike any other nation’s capital: a modern city with significant public and private investment designed to attract international business and to make a good impression on visitors.

- The city is full of new construction and green spaces towards its center. The outskirts of the city give way to older Soviet-style apartment blocks while the ger districts sprawl out onto the hills.

- Mongolia's Government Palace stands in Suukbaatar Square in the center of the city, housing the office of the president, prime minister and national assembly. A grand statue of Chingiss Khan stands at its front entrance, flanked by his generals Muqali and Bo'orchu.

- Most of Ulaanbaatar's exterior signage is either in English or in Mongolian and English, so for someone like me visiting, it isn't hard to figure out where I was going. Like other parts of Asia, Yum Brands restaurants have a conspicuous footprint (Pizza Hut, KFC, and in an inronic twist, Lucky Sheep Mongolian Hot Pot, a Chinese brand acquired by Yum a few years ago). I went to a local KFC on a desperate late night when nothing else was open; the quality was leagues better than you'd find in the USA.

- Tom N Toms, a Korean company, is more or less the Starbucks of the city, with locations on nearly every corner. As I've experience in other parts of Asia, there is no drip coffee, and you get sort of an odd look when ordering when an Americano with no milk or sugar.

- One year ago, the city began to host the Nightlight Street event each weekend on a section of Seoul Street in the western part of downtown Ulaanbaatar. Here, about a half kilometer of street is closed off and lights are draped overhead. Thousands of people relax to eat street food and drink beer every Friday and Saturday night. When opened, it was declared the first car-free street in Ulaanbaatar. As a central part to Ulaanbaatar's nightlife, I found myself back here three or four separate evenings during my stay.

- No matter where you are in the world, you are near an Irish pub. In this case, I'm enjoying a pint of Chinggis (Genghis Khan) beer. Many things in this country are named after him, including the airport, this beer, a perfectly serviceable vodka that was only a few US dollars per liter, a major city thoroughfare, about a hundred restaurants including the one I am drinking this beer in and more than one bank. Though famous internationally for building the largest empire in human history, the Great Kahn is also largely individually responsible for establishing a united Mongolian identity. Nearly a thousand years ago, he brought disprate tribes together into a singular nation through his brilliance, diplomacy, cunning and ruthlessness, and one can draw a straight line from him to the culture that is largely intact to this day. I have to think that his role in bringing Mongolia together is probably more important to the people here than his foreign conquests, and that is why the country honors him. And so, he persists as the nation's cultural hero to this day

- I had seats in the house for what turned out to be just about the most astonishingly gorgeous music I've ever heard. Various classical and original pieces were performed with an orchestra of mostly morin khuur, the national instrument of Mongolia. It is kind of like a violin with two long strings instead of four.

- The soloist astonished me with his talents by performing Ave Maria entirely with overtones produced via throat singing. The orchestra behind him performed harmonies so lush I couldn't make sense of how they worked. The costumes were gorgeous and the entire ensemble changed outfits several times to fit the music. I can't say that his throat singing overtones produced the most beautiful version of Ave Maria I've heard. To be honest, the musical texture between the orchestra and his overtones was extremely odd. However, he was showing off, and the audience knew it, and as soon as he finished every single person in the theater sprung immediately to their feet.

- . . . and an exterior view of Mongolia's National Academic Drama Theatre, in which I saw the show mentioned above.

- A view of the city from Zaisan Hill, a popular spot on the south side of the city. The hill was full of tourists, dating couples and families coming to enjoy the view and street vendors hoping to part you with your hard-earned money on dart throwing games and other novelties. With such a sweeping vista, I can see why it was a popular spot. I even returned here a second time at night.

- In the distance, the ger districts sprawl onto the hills surrounding the city. There about a third of Ulaanbaatar's population live in a gers at the nexus of Mongolia's traditional nomadic and modern city lives.

- It was not uncommon to find falconers and their golden eagles at tourist sites in the city and countryside alike. Falconers entered Mongolia fleeing Kazakhstan during the Soviet period, and as a group, simply never ended up returning home.

- For the next five years, Mongolia became a battleground for powers both foreign and domestic, trading hands between Bogd Khan loyalists, Chinese forces, anti-Bolshevik Russian revolutionaries and ultimately the Soviet Union. The Soviet-backed Mongolian People’s Republic was established in 1924. It functioned in almost all respects as the 16th unofficial republic of the Soviet Union. Mongolia was, at least officially, a sovereign nation and served for much of the 20th century as a strategic buffer between Soviet and Chinese territory.

- Tsetserleg, capital of Arkhangai province, population ~15,000. This photo provides a pretty typical example of life in towns and villages outside of Ulaanbaatar. Aside from some gers and a good deal more dust, it did not feel much different than the small towns in Wisconsin where I grew up—including the tourists, of which there were plenty, stocking up for the own journeys through the steppe. There were, as always, animals everywhere. In this case, horses and yaks, the latter of which I was told the region is known for. Here I purchased a sack of aaruul, or dried curd, at the supermarket. It's a little bit like a very dry and crumbly cheese, and it was the same thing I had in Kazakhstan (though there and in most places that I know of it is called "qurt"). I have to say, though, that what I had is much better in Mongolia.

- Through the entire steppe there was usually cell service with somewhat brief gaps between settlements. I would probably rate the wilderness coverage on the Mongolian steppe much better overall than that of Wisconsin's northwoods or much of rural America. My line of work in my day job leads me to take particular interest in celullular coverage in rural or wilderness areas. Maybe the United States should look to carriers in Mongolia for guidance.

- Sukhbaatar Square, named after the hero Damdin Suukhbaatar, the hero of the Mongolian Revolution of 1921 that established Mongolian independence.

The Ger

- The ger, a type of yurt, is the traditional dwelling of the Mongolian nomad, and they are ubiquitous throughout the country to this day. Though most of central Asia shares a tradition of nomadic life, Mongolia is unique in that the ger is still a part of daily life.

- You will see them everywhere--ringing the city and villages, dotting the countryside, at tourists camps and all manner of unusual circumstances.

- In once case, I even saw one on a city rooftop.

The Biggest Damn Stainless Steel Statue in the World

- Nowhere is the display of Mongolia's cultural hero Chingiss Khan displayed with less subtlety than this 40-meter-tall statue outside of Ulaanbaatar, which I believe is the largest stainless steel statue in the world (or, at the very least, the largest equestrian one).

- You can climb to the top and fight with tourists to get a photo of his face . . .

- . . . or appreciate the spectacular view of the steppe.

- In customary fashion, the grounds are populated with (human-sized) statues of warriors in the same sort of armor they would have worn during the great khan's time.

My Squad

- I owe Khishigee a debt I doubt I can ever repay. I had the time of my life during my visit in Mongolia, and I largely have her to thank for it. She joined me nearly every day in the country, organizing everything and introducing me to an ever-growing cast of characters that I am now happy to call friends of my own.

- With a local best friend at my side, I was able to negotiate all sorts of things I would have never been able to manage on my own, whether it was crowding into a tiny ger to order khuushuur at the horse races during Naadam, an impromptu road trip nearly to the Kazakhstan border or finding a karaoke place in a dark alley at 1:00 AM that had a reasonable English language song selection and a good deal on entire bottles of vodka. The rare days we didn't meet, she always checked in to make sure I was ok. Since I have returned home from my trip, I've missed her terribly. For the gift of the experiences I've had, I owe her everything.

In Closing

- Mongolia was not only the most beautiful place on Earth I have visited, but one of the most humbling. Even though I was in the custody of good friends in a relatively tourist-friendly country during peak tourist season, I was always completely out of my element. For nearly entire days at a time, I navigated in relative silence, unable to really communicate and just getting by. I wish that my trip, much like the steppe, would have never ended; unending, indominatable and permanent.